When I first met my wife, we connected over our mutual love for ethnic foods. She had lived in Korea before and I learned about Indian food from a close friend in college. One of our first dates was to a local Korean restaurant in Portland Oregon where we lived. The restaurant was Sokongdong, on the east side of town, just off 82nd street. I loved it, and we returned many times. But one dish really peaked my interest, a soup called yukgaejang. A delightfully spicy dish featuring shredded beef. The worst thing about it is upon coming to Korea I haven’t enjoyed a yukgaejang as good as the one I had at Sokongdong. I expected glorious things from the native land, but even while the versions I’ve had here are somewhere on the spectrum of OK to good, nothing has compared. None have been as spicy, with beef as quality, or with a mouth watering layer of chili oil swimming on top of the bowl. I won’t give up my quest though. This is how I got good at Indian food. I tried my friend’s mother’s dishes and sought to recreate them until I could. Perhaps the time has come to add Korean cooking to my ethnic cuisine repertoire. My wife is already really good at many Korean dishes, but I have my favorites that I’d like to perfect, and yukgaejang tops the list.

After several disturbing experiences I’ve had in Christian organizations over the years, I have developed the habit of asking myself a question: what’s Christian about this organization? Is it just the name? Is it what they believe? Is it the market they serve? What are the key indicators to how Christian an organization is? I ask this of churches too. I believe there are many Biblical principles that can be in place in any organization, but the real litmus test of how Christian an organization is is how much the Gospel is a part of who they are and what they do. This goes beyond mere statements, and must be an actively sought after part of the lives of the people and the culture they create.

Even if it’s part of the organizational culture to say “Gospel” all the time with no theological clarity to it, it will never gain real traction. Even, “Jesus died for my sins” can be used in such a generic way that the actual helpfulness, the culture creating power of the details of that truth, can be substantially minimized or entirely diminished under the weight of so many other culture creating ideas that vie for the ideological rule of the organization. In some cases this minimization and diminishing is spiritual abuse, but that’s a focus for another post.

I’ve worked for churches, parachurch organizations and in Christian business as well. Now I work for a Christian school, with my chief focus on Christian Education. I wouldn’t claim to know everything on this issue, but here is something that I do know. Without a pervasive active awareness of our justified state in Jesus Christ, awareness that we are free from the eternal penalty of sin because Christ has paid it, an awareness that permeates everything we do, then we are somewhere on the spectrum of a weak Christian organization to not one at all.

Specific to spiritual formation, justification through faith is foundational, such that without it admin, teachers and students are all either teaching or learning something contra Christian without it’s active presence. I say active because the worst thing that usually happens is assuming this is part of the belief and culture of a “Christian” organization without actively seeking out whether this is true or not, and what should be done to ensure it is. This takes different shapes in the different contexts of a school.

From an administrative perspective, it must become part of what guides every decision. Will a decision lead to stronger unity and clarity around our justified state as followers of Christ? Will what we do magnify or diminish that reality in our lives? In what manner should all the business of the school be done? Are we doing it in a way that drips with the reality we are living in, of being graciously justified by Christ dying on the cross for our sin, and are we handling our affairs in a way that points to that? Sometimes it’s easy to connect these dots, often it is not. When speaking in a devotional, or leading meetings, it’s easy to communicate directly, to speak in a way that builds a clear understanding of justification into the identity of the school. When handling a tough human resource issue, how does a leader thread the needle of correction and care? It’s definitely a challenge, but one that must be faced head on in the light of a school’s identity as a Christian one.

From a teacher’s perspective, classroom management and curriculum design are big burdens. Doing them well at all is a skill that takes practice and a lot of trial and error. I know I am still learning so much each class I question whether I should teach at all sometimes, especially in an ESL environment. Nevertheless, the challenge is to do it all in a way that is soaked in the truth that we, and all those who trust in Christ are, free from the eternal penalty of sin because we are justified in Christ because of his perfect life, unjust death, miraculous resurrection and well-witnessed ascension to Heaven where he is ruling and reigning today. Do I lead my class in that reality? When I need to punish a student, am I doing it in a way that leads them to believe that even though they are misbehaving, God still loves them such that he sent his Son to die and justify them before him on the day of judgement? It’s a question that is hard to default to in the moment, but again, it’s a distinctively Christian way to handle the moment, and a challenge we face willingly to maintain our identity as a truly Christian school doing distinctively Christian spiritual formation. Does our curriculum do anything to diminish the reality of our justification? Are we teaching anything that would diminish that truth in our students lives? Is there any way, though not all subjects are created equally ripe for direct communication on this point, that we can build this reality in our students through our curriculum? I will leave it to the experts in their fields to determine if this is possible and if so how easy it is, but as a Bible teacher I cannot get away with failing to build this into my curriculum and still call it a Christian curriculum. I would say for other fields, science, language, math, art and history, a clear goal would be to do nothing with the curriculum that takes away from that reality even if it would feel arbitrary to do any direct teaching on the subject of justification. But I would encourage prayerfully looking for any opportunity to highlight areas in your specialization that might naturally draw attention to Christ’s work of justifying us before God.

A few years ago, before I got married, I got some counseling. There were issues I was carrying with me from childhood that were affecting my relationship with God, and along the way there was no short supply of baggage life had help me accumulate on top of that. I wanted some help before I even thought of marrying anyone, and once I met the woman I wanted to marry I sought all the help I could get. As part of the process I wrote this following poem. A big part of my problem was trusting God’s love for me, and a healthy focus on his justifying work in my life was a big part of a lot of emotional healing after living under many lies that people had led me to believe, and I had taken on as part of my identity. I don’t consider myself a poet, I just know it’s good to read and try to do sometimes. I also want to be clear this isn’t just a head exercise for me, but something I’m deeply and emotionally invested in.

Yes, Jesus Loves Me…

Jesus loves me

This I

forgot,

For it was man’s esteem

That I have sought.

Christ would hand me

His identity to receive,

But I

foolishly

Have worked to achieve.

As a little one To Him I RAN!

But

I

Have

Slowed

To

A

crawl

As a man.

I am so weak,

And the days are long.

I am

weak,

But He is STRONG!

Does He love me?

This

wretched man;

Does He love me

as I am?

In spite my sin and shame,

He’s done what a savior must:

He died in my place,

And has declared me just.

“But God demonstrates his own love for us in this: While we were still sinners, Christ died for us.” (Ro 5:8)

Justification.

The act of God in bringing sinners into a new covenant relationship with himself through the forgiveness of sins. Along with such terms as “regeneration” and “reconciliation,” it relates to a basic aspect of conversion. It is a declarative act of God by which he establishes persons as righteous; that is, in right and true relationship to himself.Elwell, W. A., & Beitzel, B. J. (1988). In Baker encyclopedia of the Bible (p. 1252). Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House.

JUSTIFICATION Divine, forensic act of God, based on the work of Christ upon the cross, whereby a sinner is pronounced righteous by the imputation of the righteousness of Christ. The doctrine of justification is developed most fully by the Apostle Paul as the central truth explaining how both Jew and Gentile can be made right before God on the exact same basis, that being faith in Jesus Christ. Without this divine truth, there can be no unity in the body of Christ, hence its centrality to Paul’s theology of the Church and salvation.

White, J. (2003). Justification. In C. Brand, C. Draper, A. England, S. Bond, E. R. Clendenen, & T. C. Butler (Eds.), Holman Illustrated Bible Dictionary (p. 970). Nashville, TN: Holman Bible Publishers.

justification. In dogmatic theology, the event or process by which man is made or declared to be righteous in the sight of God. Despite the suggestion of the etymological form of the Latin verb justificare (justum facere, ‘to make righteous’), it is widely held that in the NT (and esp. in St *Paul) the Greek δικαίωσις and its cognates reflect Hebrew usage, and are thus to be understood as legal metaphors signifying ‘vindication’ or ‘declaring to be righteous’. St *Augustine, however, interpreted the Latin term iustificatio to mean ‘making righteous’, thus establishing a tradition which remained unchallenged until the end of the Middle Ages. At the time of the *Reformation, controversy surrounded both the meaning of the term, as well as the means by which justification comes about. In classical *Protestant theology, ‘justification’ was interpreted as God ‘declaring man to be righteous’ (thus recovering the sense of the original Hebrew term), to be distinguished from sanctification, in which man is ‘made righteous’. The Council of Trent defined justification in strongly transformational terms, rejecting the Protestant understanding of the concept. In both *Lutheranism and *Calvinism, justification is an act of God, effected without man’s co-operation (an idea expressed in formulae such as sola fide (‘by faith alone’) and sola gratia (‘by grace alone)). According to the Council of Trent, justification requires man’s co-operation with God. A further difference of importance concerns the formal cause of justification, which Protestants held to be the imputed rightousness of Christ, and Trent defined as the inherent or imparted righteousness of Christ. Much Anglican theology has followed the Calvinist tradition on this point, though classical High Anglicanism of the 17th and 18th cents., while affirming that man is justified by grace through faith, insisted that he must also labour for salvation, doing the good works prepared by God for him to walk in. Recent ecumenical disussions have suggested that many of these distinctions are verbal rather than substantial, with the result that a degree of consensus on the doctrine has emerged, for instance in the Agreed Statement of the Second *Anglican–Roman Catholic International Commission (1987). However, the biblical roots of the doctrine have been challenged by some NT scholars whose interpretation of Pauline theology, and the function of justification language within it, have cast doubts upon traditional (esp. Lutheran) accounts.

Cross, F. L., & Livingstone, E. A. (Eds.). (2005). In The Oxford dictionary of the Christian Church (3rd ed. rev., pp. 919–920). Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

JUSTIFICATION—a forensic term, opposed to condemnation. As regards its nature, it is the judicial act of God, by which he pardons all the sins of those who believe in Christ, and accounts, accepts, and treats them as righteous in the eye of the law, i.e., as conformed to all its demands. In addition to the pardon (q.v.) of sin, justification declares that all the claims of the law are satisfied in respect of the justified. It is the act of a judge and not of a sovereign. The law is not relaxed or set aside, but is declared to be fulfilled in the strictest sense; and so the person justified is declared to be entitled to all the advantages and rewards arising from perfect obedience to the law (Rom. 5:1–10).

It proceeds on the imputing or crediting to the believer by God himself of the perfect righteousness, active and passive, of his Representative and Surety, Jesus Christ (Rom. 10:3–9). Justification is not the forgiveness of a man without righteousness, but a declaration that he possesses a righteousness which perfectly and for ever satisfies the law, namely, Christ’s righteousness (2 Cor. 5:21; Rom. 4:6–8).

The sole condition on which this righteousness is imputed or credited to the believer is faith in or on the Lord Jesus Christ. Faith is called a “condition,” not because it possesses any merit, but only because it is the instrument, the only instrument by which the soul appropriates or apprehends Christ and his righteousness (Rom. 1:17; 3:25, 26; 4:20, 22; Phil. 3:8–11; Gal. 2:16).

The act of faith which thus secures our justification secures also at the same time our sanctification (q.v.); and thus the doctrine of justification by faith does not lead to licentiousness (Rom. 6:2–7). Good works, while not the ground, are the certain consequence of justification (6:14; 7:6).

Easton, M. G. (1893). In Easton’s Bible dictionary. New York: Harper & Brothers.

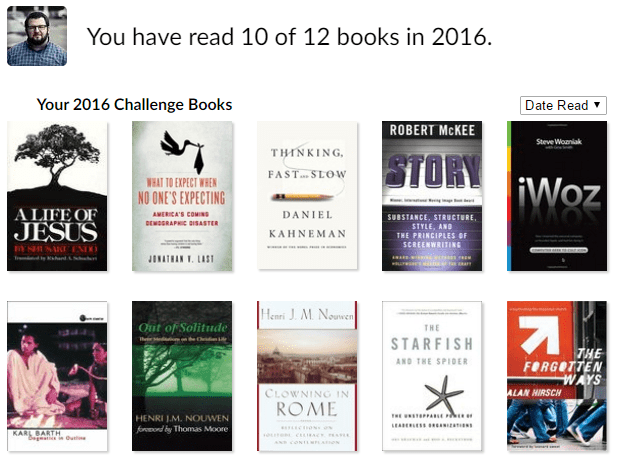

Last year I started tracking my reading goals, successes and failures with a couple of friends using Goodreads. I set the not so lofty goal of reading two books a month, but moving across the world and starting a new career cut me pretty far short of my goal. I sought to set a more modest goal this year and I know I’ll meet it. One book a month is really nothing. I’d love to get to a book a week, and I’d love to write more as I’ve stated not too long ago. I know some people who read 100 books a year. I’m jealous. It’s going to take some real commitment or becoming a full time student again to get to that point I think.

While I enjoyed most of the books, only the last one in the ranking ended up being a real disappointment. So here’s my ranking with brief explanations.

I really enjoyed this book. I had been wanting to read it for a long time because I want to know more about screenwriting and what the methods were behind really good stories on film and TV. I was not disappointed. It’s very straightforward and technical but also fun, because the subject matter is always interesting. Even though it takes a lot of practice to get good at it, everyone can relate to the innate sense of knowing when a story is good or bad, and this book gets a little in to the details of why that is, and how to harness that for your own writing. It’s specific to screenwriting, though many principles will be applicable to any writing I believe. A big book, but a lot of fun if you like film and/or stories.

I enjoyed this book a lot more than I thought I would. Having read two other books connected with the legacy of Steve Jobs before this, I just wanted a bit more perspective on the personalities behind the Apple phenomenon. But what I found in Wozniak was a relatable guy caught up in a world of power. I felt a lot more pathos from his account than I planned to. Having worked in tech and seeing how poor relationships can be in any organization, especially with a lot of youth and ego, I found Woz to be a bit of a mentor while much of the world tries to emulate Jobs. Woz was a good friend. Every time I read a book on Jobs or watch a documentary, I’m impressed just like everyone else, but I wouldn’t want to work with or for him. When I read about Woz I feel like he’d be an incredible guy to work with or for. His version of events is much more emotional and lighthearted, and I really appreciated his wisdom.

3. Dogmatics in Outline by Karl Barth

Barth is theological force to be reckoned with. This book of his though, is very accessible. He definitely deals with deeper theological issues, but this short 150 page book was derived from lectures he gave to lay leaders in German churches. If this were the only thing he’d written I don’t think there would be much controversy regarding him. But he went on to write much, including his massive “Church Domatics,” which perhaps I’ll read one day. As an introduction into his thought, I really enjoyed this quick little read, and I found it helpful for the same kind of people today he was speaking to then, lay church leaders.

4. The Forgotten Ways by Alan Hirsch

Alan Hirsch is one of the most popular authors and speakers of the missional church movement, and this was his breakout book. I had read bits and pieces of his books for years but I wanted to finally finish this one, and I’m glad I did. I enjoyed it a lot, but I do have a growing concern that the missional church movement has become excessively works oriented and tribal. There’s an entire subculture of missional churches now that have a language not shared with much of the Christian world, and rituals and practices that wouldn’t be recognized by much of the global church, including places like China, which Hirsch references a lot, where the church is growing rapidly while under oppression. I fear this is becoming a trendy way to do church for white hipster evangelicals more than anything else. That’s not a bad thing, because the goal is good, but I think there is a sanctioning of sub-cultural lingo and practice that is used as a judgment of spiritual character, when those things are best left on the spectrum of possible appropriate adaptations to cultural contexts. All that said, it’s a good read with good challenges to an all to stagnant western church.

5. What to Expect when No One’s Expecting by Jonathan Last

I was just curious about this one after seeing it on a reading list by Pastor Tim Keller. It ended up being a fascinating look into the issue of fertility around the world, and particularly in America. The primary concern of the book is the impact of various sociological forces that lead to many things, one of them primarily being a dearth or growth of baby making, and what it tells us about the American political environment. In many ways it’s a timely read for an election year such as this. I don’t know enough about demographics and sociology to critique anything Last says, but that being said, I really enjoyed reading it, and I want to read more books like it in the future.

6. Clowning in Rome by Henri Nouwen

Nouwen was a prolific Catholic writer for many years, particularly in the genre of spiritual formation. This book is a collection of lectures he gave in Rome to a group of clergy people. He took his cues from the clowns around Rome who he viewed on the periphery of society, very humble, yet whose live’s entire purpose was to bring a smile to people on the periphery. That’s the major theme, the clownishness of the Christian life as a way of standing against the worldly powers. It’s an interesting and humble read, and I felt humbled by reading it. Nothing too heady, just a reminder that we’re all clowns, and to do the best with that we can. Who can’t use that reminder from time to time?

7. Out of Solitude by Henri Nouwen

Another short one by Nouwen just focused on solitude. It was yet again a very simple reminder, this time on the importance of being alone as a spiritual discipline. In a noisy world, it’s certainly a hard practice to cultivate, but his wisdom was a welcomed reminder to put up that fight for the sake of spiritual health.

8. The Starfish and The Spider by Ori Brafman and Rod Beckstrom

I had been aware of this book for the better part of a decade before finally getting around to reading it. It’s on decentralization in organizations and movements, with a lot of case studies from history to modern times. In many ways it is a secular version of the Forgotten Ways, Hirsch even sites it in the book. It’s a helpful book on the power of culture and ideas, and how when those are the things that unite people for a long period of time, the staying power is enormous. The title captures the idea well, if you cut the leg off a starfish, another starfish is born, but if you get the head off a spider it dies. It’s pretty much that simple, but requires a lot to make it apart of your organizational culture.

9. Thinking Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

I enjoyed this book, but it was just too long. There is a lot of narrative about how much leisure time the author as an awesome scholar had to run all his thought experiments, when he should have dived into the fruit of that labor a lot more quickly. Even so, the fruit of his labor is very fascinating, and quite helpful to me as a teacher. Basically his research highlighted how powerful human instinct is, fast thinking, and how we don’t really appreciate that enough. However, it needs to be reigned in under the discipline of slow thinking, and careful reasoning. The real key is developing the skills associated with how to switch back and forth depending on the context. A very interesting if not overly long read.

10. A Life of Jesus by Shusaku Endo

I read this book for two reasons. One was that it’s a popular book from a Japanese author about Jesus. This is significant for many reasons. One being that Japan is less than 1% Christian. This book is older now, but Endo wrote it as a help to Japanese people to understand and empathize with Jesus from their cultural perspective, so I really read it for that insight. I’m quite familiar with the life of Jesus, but living in Korea, I don’t know enough about what Korean culture specifically, or Asian culture more generally, find most appealing about him. I know it’s different from the West in at least some ways. I wanted Endo to shed whatever light he could on that cultural note in his telling. Secondly, I wanted to read this because another book he wrote, “Silence,” about Jesuit missionaries being persecuted in Japan a long time ago, is being made into a movie by Martin Scorsese soon, staring Liam Neeson. So I wanted to see what this guy had to say about Jesus. The reason I came away disappointed is because he was heavily under the influence of German higher criticism. He quoted Bultmann a lot, as well as other mid-century German textual critics of the Bible. In the end, he didn’t believe in a real resurrection of Christ, but instead a very humanistic interpretation I’ve read in other liberal theology, that Jesus’ legacy rose in the lives of his followers such that it lived in them, and in that way, he was resurrected. Along the way, I didn’t feel like I gleaned much cultural insight from him either, so I left feeling pretty disappointed and sad. If he’s one of the few Japanese authors who wrote about Jesus, I can’t be surprised Jesus isn’t a bigger deal there. I have several friends who are missionaries in Japan, and I pray that they will lovingly teach and correct this where it is found.